Court History

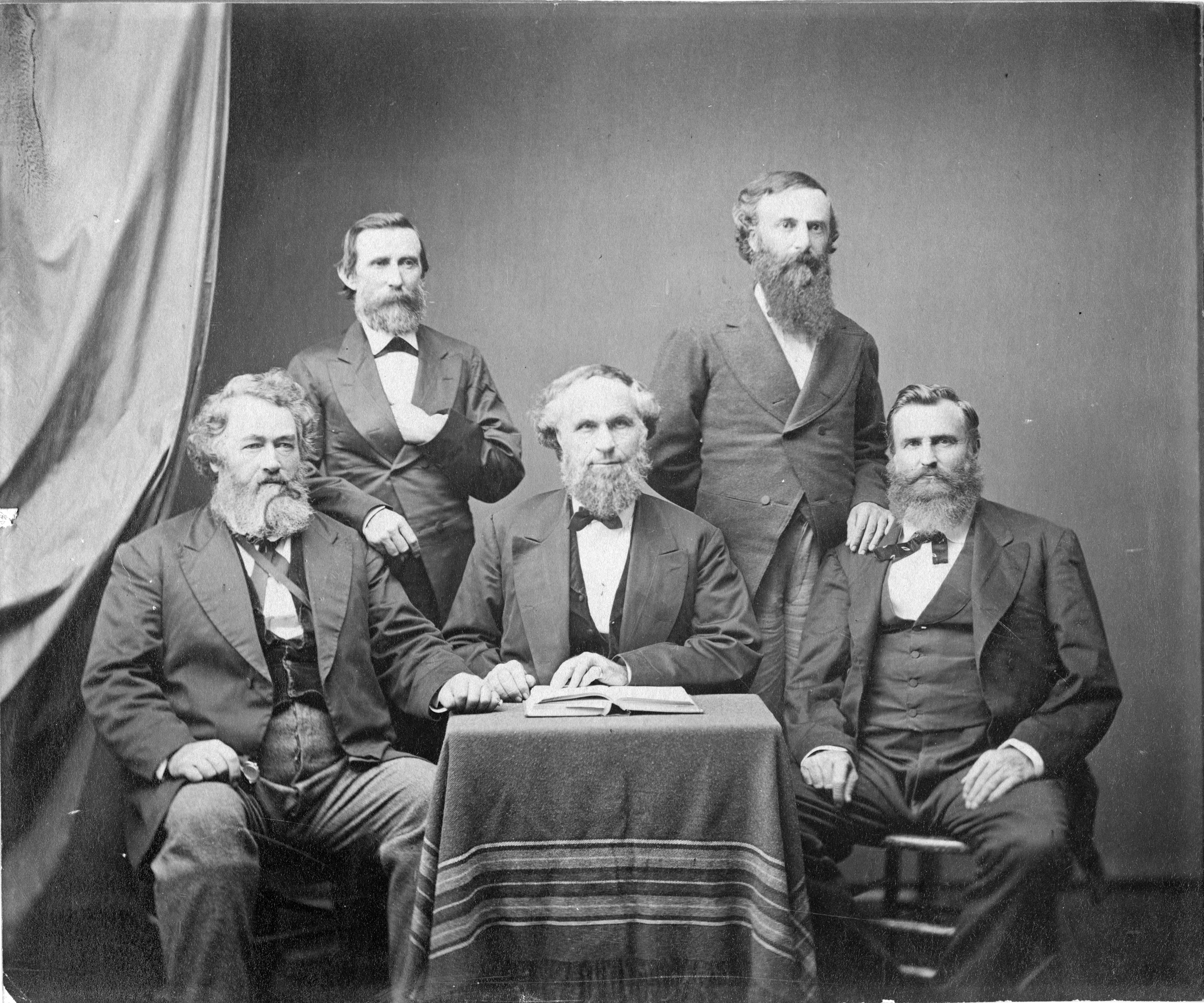

The “Semicolon Court” (seated left to right, Justice Moses B. Walker, Chief Justice Wesley Ogden, Justice J. D. McAdoo), with E. M. Wheelock (standing left) and Clerk W. P. DeNormandie, 1874. Photo: Austin History Center.

"Semicolon Court" is the label given to the Texas Supreme Court that sat between 1870 and 1873. It was applied by contemporary lawyers as a result of the importance this court attached to a semicolon in its decision in Ex parte Rodriguez. Because Rodriguez nullified the election of Democratic gubernatorial candidate Richard Coke, who took office despite the court's decision, subsequent opinions of the court have been highly critical. Lawyers and politicians in the late nineteenth century coined the epithet Semicolon Court in derision. Oran M. Roberts, who served on the court after 1873, gave the term historical permanency when he used it in his history of the Reconstruction era, the first serious and comprehensive account of the state during this period. Roberts concluded that the court was in such disrepute that the legal profession did not even like to cite its decisions.

The court that earned such general disapprobation was convened by the authority of the Constitution of 1869. Article V established a court of three judges, one to be named chief judge, appointed by the governor with the advice and consent of the senate. The term of each judge was nine years. The new constitution ended the practice of a Supreme Court circuit and required annual sessions to be held at Austin. Republican governor Edmund J. Davis appointed Lemuel D. Evans, Moses B. Walker, and Wesley B. Ogden the first judges for the term that began in December 1870. Evans served as chief judge. The three drew straws to determine the length of their terms, and Evans drew the three-year term. When he stepped down in 1873, he was replaced by John D. McAdoo, and Justice Ogden became the chief judge. The men who served on the Semicolon Court were all attorneys with lengthy experience in their profession. Evans was an old Texan who had served in the Convention of 1845 and as congressman from the state's eastern district in the Thirty-fourth Congress. After the Civil War he was a member of the Constitutional Convention of 1868–69. Ogden had been a lawyer in San Antonio and had served as a United States district attorney and a state district judge. McAdoo, a Confederate veteran from Brenham, had been a district judge. Walker was from Ohio and was therefore one of the few prominent officials in the Davis administration who could be called a carpetbagger. Walker had served previously on the Texas Supreme Court during Military Reconstruction.

In this court's four regular terms, its members considered numerous important cases with political implications. In these cases they proved themselves independent. The court upheld the Davis administration's unpopular school-tax program in Kinney v. Zimpleman, Texas v. Bremond, Hall v. Houston and Texas Central Railway Company, and Peay v. Talbot and Brothers. On the other hand, the justices upheld the grant of land in 1866 to a railroad controlled by prominent Democrats in Houston and Great Northern Railroad Company v. Jacob Kuechler, while refusing to order Albert A. Bledsoe to countersign state bonds given to an administration-favored company in International Railroad Company v. the Comptroller. The strongest stand taken against Governor Davis came when the court upheld the right of George W. Honey to remain state treasurer after the governor had declared the office vacant. In Honey v. Graham the court found that no elected official could be removed by gubernatorial proclamation.

Previous independence, however, could not counteract the damage done to the reputation of the court in Ex parte Rodriguez. In this case the court invalidated the general election of 1873 on the grounds that the law providing for the election did not meet constitutional specifications. The Constitution of 1869 had provided in Article III, Section 6, that all elections would be held "at the county seats of the several counties until otherwise provided by law; and the polls shall be opened for four days." For the 1873 election the legislature provided that polling would be held in precincts and the polls would be open for only one day. The court ruled that the semicolon in this section made the second clause of the provision independent, thus not open to a change by the legislature. The court's ruling made the election unconstitutional. Opponents of the Republican administration considered the decision to be political rather than based on the merits of the case, since its effect would be to keep the Davis government in office. Among Democrats the Semicolon Court was thereafter viewed with hostility. The decision in Rodriguez was never enforced. Davis refused to use the police powers of the state to uphold it. Coke chose to ignore it and seized power from the existing government in January 1874. His takeover ended the Semicolon Court, since he immediately implemented the constitutional amendment, also passed in the disputed election, that increased the number of judges to five and allowed the governor to appoint new ones. Coke removed the sitting justices and appointed an entirely new court.

Although Roberts observed that the Semicolon Court's decisions were not respected by the legal profession of the state, its actions did become a part of the legal corpus of the state. Post-Reconstruction justices, including in one instance Chief Justice Roberts himself, declined to hear cases challenging two railroad subsidies in Kuechler v. Wright and Bledsoe v. International Railroad Company. Roberts also cited precedents from this court in decisions such as Renn v. Samos and Ellis v. McKinley. Ultimately, though the court received opprobrium for Rodriguez, the bad reputation of the Semicolon Court derives largely from contemporary politics rather than from a nonpolitical assessment of its merits as a judicial body.

From the Handbook of Texas Online, Carl H. Moneyhon, "Semicolon Court."